NO, for poor

the internet gurus and venture capital investors who drive from Pittsburgh’s newly refurbished international airport to the “Golden Triangle” commercial district pass right by The Hill, but rarely catch a glimpse of it.

The Hill is Pittsburgh’s woeful secret, a dark inversion of the city’s loudly hailed prosperity which has sunk to new depths of poverty even as the suburbs around it have grown rich. A secret that reflects a wider, national failure.

The old district used to be Pittsburgh’s hallway, inhabited by successive waves of immigrants – Russians, Poles and Jews. Tradition has it that Trotsky made speeches there to raise support for permanent revolution. He would doubtless point to it now as proof of the inequities of unbridled capitalism.

The Hill’s residents these days are almost all black and the black unemployment rate, at 12%, is almost three times the white rate.

In the days of “big steel”, the district boomed along side white Pittsburgh. There were rows of bars and restaurants where Lena Horne, Art Blakey and Erroll Garner performed.

Now it looks like a war zone. Howard Jackson grew up in The Hill, but escaped before it plunged into its present despair. “Things are changing all around and The Hill is just stagnating. The city is developing. On The Hill it’s just being left to die,” he said.

But The Hill’s problems are more or less the same as impoverished districts across the country. American towns and cities have failed to take these areas on their journey from old economy to new, and the gap in family incomes between the rich and poor across the US is growing.

Jeanne Berdik of Pittsburgh technology council said: “If you’re moving to a system which requires a higher level of skills and knowledge and the state is not able to retrain people, there is going to be a bigger gap between those who have the right kind of knowledge and those who don’t.

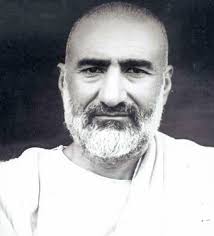

BACHA KHAN

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan Pakhtoon ke siasi rahnuma ke tour par mashhoor shaksiyat hain jinhon ne Britannia dour mein adam tashadud ke philosophy ka parchar kia. Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan zindagi bhar adam tashadud ke hami rahey aur Mahatma Gandhi ke baray maddahon mein se aik thay. App ke maddahon mein app ko Bacha Khan aur Sarhadi Gandhi ke tour par pukara jata hai.

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan Pakhtoon ke siasi rahnuma ke tour par mashhoor shaksiyat hain jinhon ne Britannia dour mein adam tashadud ke philosophy ka parchar kia. Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan zindagi bhar adam tashadud ke hami rahey aur Mahatma Gandhi ke baray maddahon mein se aik thay. App ke maddahon mein app ko Bacha Khan aur Sarhadi Gandhi ke tour par pukara jata hai.

App 1890 mein Utmanzai mein paida huye. Ibtedai taleem ghar per hasil ki. Baad mein Mission High School Peshawar mein dakhil huye. Aik saal Aligarh mein bhi guzara. Garmiyon ki chutiyon ke liyeh waten wapas aye to taleem adhori chor di. Britannia foj mein shamuliyat ka shouq huwa. Bacha Khan ko Foji officer ki wardi pehenne ka shuq tha. Iss zamane mein ala Musalman gharano ke noujawano ko horse riding daston mein Junior Commissioned Officer liya jata tha. Abhi shamuliyat ikhteyar na ki thi ke unhon ne aik roze apney dost ko alla Angrez officer se jhar partey dekhi iss per Angrez ki nokri se nafrat ho gaye.

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (Bacha Khan) ke barey bhai Abdul Jabbar Khan(Doctor Khan ) Englishtan mein thay unhon ney Abdul Ghaffar Khan ko waheen bolaya lakin Walid Sahib ney janey na deya keonkey Doctor Khan Sahib ne waheen molazmat ikhteyar ker ke aik Angrez Khatoon se shadi ker li thi aur un walda ka kheyal tha ke bara beta to hat se geya ab chota beta bhi waheen jaker kisi Angrez larki se shadi karey ga aur waheen ka ho rahey ga. Iss tarah Bacha Khan taleem ke liyeh baher na jasake.

1911 mein Angrezon se nabro azma mashoor mojahid Haji Sahib Turangzaiki tahreek se wabista hogaye. Haji Sahib ne Sarhad bhar mein 72 Madrase qaim keya jo unki tehreek jehad ke marakez they. 1913 mein Haji Sahib Tarangzai Qabaili Ilaqon mein apna markaz qaim kerne ke liyeh muntaqil hogaye. 29 saal ki umer tak Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (Bacha Khan) khamosh karkun ki hasiat se rahe lakin 1919 mein jab Rowlatt Act ke khelaf Bare Sagheer mein tehreek chali to unki khatibana salahiatein zahir huyein natijatan griftar hogaye aur 1924 mein reha huye. Issi bares hijrat ki tahreek chali to Bacha Khan bhi bohot se satheon ke sath Kabul Hijrat ker gaye. Tehreek hijrat halaat ki sangini se takrao to Bacha Khan bhi dusre mahajreen sameat iss ehisas ke sath watan wapas loutay ke azadi aise jazbati iqdamat se hasil nahein ki ga sakti tahreek hijrat Haji Sahib Turangzai ke madrason ko khatam ker dala tha Bacha Khan ko teen saal ke liyeh jail mein dal dia gaya 1942 mein jail se nikley to khelafat comaitee mein kam kerte rahe.

1927 mein Ghazi Amanullah Khan ke khelaf Afghanistan mein sorish huye to Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (Bacha khan) aik wafd ke sath Amanullah Khan se mulaqat ke liye Balochistan ke raste Kandahar ja rahe thay ke unhein Sibbi mein griftar kar liya gaya. 1930 mein sarhad mein Angrezon ke khelaf azadi ka ahang intehai taiz ho gaya Qissa Khawani Bazar mein firing huye hazaron ki tadad mein Pakhtoon shaheed kiye gaye Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (Bacha Khan) ko Atmanjai se Peshawar atey huye griftar ker liya geya aur agley 7 saalon mein Abdul Ghaffar Khan sirf chand mah jail aur nazar bandiyon se azad reh sake.

Bartanwi Raj ke khelaf kai bar jab tahareek ko nakami ka samna kerna para to Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan ne imrani tahreek chalane aur Pashtun Qabail mein islahat ko apna maqsad hayat bana liya. Iss soch ne unhein South Asia ki aik nehayat qabil ziker tahreek khodai khidmatgar tahreek shuru kerne par majboor kiya. Iss tehreek ki kamyabi par inhein aur sathiyon ko kai bar tashadud ka nishana banaya gaya aur paband slasal kiya gaya.

1931 mein app jail se chutey to issi baras phir Mount Marlow islahat ke khelaf tahreek chalane ke jurm mein pandrah hazar razakaron samait griftar huye. Issi baras badtareen hotey hueay halat mein unhon ne Mahatma Gandhi aur Indian National Congress ke sath ilhaq kar dea jo iss waqt adam tashadud ki sab se bari hami jamat tasauar ki jati thi. ye Alhaq 1947 mein azadi tek qaim raha. South Asia ke mumalik ki azadi ke bad Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan ko noble iman ke liye bhi namzad keya geya.

1934 mein rahai pai to un ka Punjab aur Sarhad mein dakhla mamnun qarar diya. Ye woh dour tha jab Khan brothers Gandhi ke qareeb aye Sait Jamnalal Bajaj ne unhein apne haan Warda aney ki dawat di. Unhein dinon Gandhi Ji bhi waheen moqeem thay. 1935 mein Sarhad anye per pabandi khatam huye to ghar aney se pashter Bambai mein griftar huye iss tarah chay baras bad August 1937 mein ghar wapis aye lakin unn qurbaniyon ka samara unhein uss waqt mila jab issi baras un ke sathi Sarhad Assembly ke pehle amm intekhabat mein pachas mein se unees nishashton per kamyab rahe. Iss ke baad azadi ki jaddojehad mein congress ke sath rahe.

1944 mein “Hindustan chor do” ki tahreek mein lathi charj ka shikar hoker app ki do paslian toot gayein. Zakhmi halat mein app ko qaid mein dal diya gaya. Jang Azeem ke khatme per app reha huye 1946 ke amm intekhabat mein Mutthida Hindustan ki markazi dastoor saz Assembly mein rukun muntakhib huye baad mein Pakistan ki dastoor saz Assembly ke rukun rahe. 1948 mein karachi mein Peoples Party ki bunyad Bacha Khan ne rakhi lakin iss se pashter ke iss nauzaidah jamat ka dhancah khara hota June 1948 mein griftar ker liye gaye. January 1954 mein reha keye gaye to Soba Sarhad mein dakhla aur naqlo harkat ki azadi na thi. Punjab ke zila Atak mein Ghour Ghashi ke moqam per moqeem rahe. Albatta iss sauran khasusi ajazat ke sath Karachi aur Murree mein dastoor saz Assembly ke ijlason mein shirkat ker tay rahey July 1955 mein pabandyan khatam huein to Sarhad aye aur Anti One Unit Front banaya ta ke One Unit ka qiyam roka ja sake. lakin one unit bana aur phir Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan aur Doctor Khan Sahib ke raste juda hogaye. June 1956 mein apney bhai Doctor Khan Sahab hi ki wazarat Aala ke zamane mein griftar ker liye gaye. Baghawat aur inteshar phelane ilzam mein moqadmat qaim huay. January 1957 mein rahai pai to National Awami party banai October 1958 mein Mashalla nafiz hua to masaibka key daur ka Agaz hua. 1960 aur 1970 ka darmeyani arsa Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan ney jailon aur jila watni mein guzara. Dekha jaye to unki pori zindagi hi jail ke chakker katte huye guzer gae . 1919 se 1964 tak koi ais arsa na tha jab app mosalsal teen saalon tak jail se bahar rahe hon.

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan ne National Congress ki hamnawai mein do qaumi nazere Musalmanon ke judagana tashkhus aur qiyam Pakistan ko kabhi tasleem nahein kiya. Qiyam Pakistan ke sath hi Pakhtunistan ke daye ho gae. 1965 mein Kabul chale gaye wahan se Al India Radio Kabul per apni taqreron zareye se Pakistan ki mokhalfat aur Pakhtunistan qaim ki tahreek chalai. Jab Russian afwaj ne Afghanistan per hamla kiya to unhon ne Afghan Mojahideen ki bhi hemayat nahein ki. Kabul mein app ne Bharti safarat khane ke sath gahre taluqat qaim rakhe.

1987 mein app pehle shakhs thay jin ko Bharti shahri na hone ke bawajudBharat Ratna Award se nawaza gay jo sab se azeem Bharti Civil Award hai. Bharat ke iss doure ke dauran unhein apni tehreek ke liye karoron rupay ki thalyan bhi pashe ki gayein.

20 January 1988 Peshawar mein Bhacha Khan ka Inteqal huya aur app ko wasihat ke mutabiq Jalalabad Afghanistan mein dafan kiya gayaAfghanistan mein iss waqt ghamsan ki jang jari thi lakin app ki tadfeen ke moqa per dono ataraf se jang bandi ka faisla huya ye baat app ki shakhsiyat ke ilaqae asro rasukh ko zahir kerti hai.

Bhacha Khan ki pehli shadi 1912 mein hue jis se Khan Abdul Ghani Khan aur Abdul Wali Khan paida huye. Dosri shadi 1920 mein huye jis se aik Sahib Zadi Yehya Jan aur Abdu Ola Khan paida huey. Agarchay Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan zindagi phar apne Pakistani hone se inkari rahey aur Pakistan ko aik “Ghulam” reyasat qarar detey rahey (Yahi waja hai key unhon ney dafan hone ke leye Afghanistan ki “Azad” Sarzamine ka intekhab kiya) iss hawale se unhein iss kitab mein shamil nahein kiya jana chahiye tha. Magar Pakistani siasat aur South Asia ki tareekh per un ke asrat se inkar nahien kiya ja sakta hai

Were there alternatives to the atomic bombings?

by Ahmad Shah Kakar , published August 3rd, 2015

As we rapidly approach the 70th anniversary of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, there have been all sorts of articles, tributes, memorials, and so forth expressed both in print and online. I’ve been busy myself with some of this sort of thing. I was asked if I would write up a short piece for Aeon Ideas about whether there were any alternatives to these bombings, and I figure it won’t hurt to cross-post it here as well.

The point of the piece, I would like to emphasize, is not necessarily to “second guess” what was done in 1945. It is, rather, to point out that we tend to constrain our view of the possibilities generally to one of two unpleasant options. Many of those who defend the bombings seem to end up in a position of believing that 1. there were no other options on the table at the time except for exactly what did occur, and 2. that questioning whether there were other options does historical damage. As a historian, I find both of these positions absurd. First, history is full of contingency, and there were several explicit options (and a few implicit ones) on the table in 1945 — more than just “bomb” versus “invade.” These other options did not carry the day does not mean they should be ignored. Second, I think that pointing out these options helps shape our understanding of the choices that were made, because they make history seem less like a fatalistic march of events. The idea that things were “fated” to happen the way they do does much more damage to the understanding of history, because it denies human influence and it denies choices were made.

Separately, there is a question of whether we ought to “judge” the past by standards of the present. In some cases this leads to statements that are simply non-sequiturs — I think Genghis Khan’s methods were inhumane, but who cares that I think that? But World War II was not so long ago that its participants are of another culture entirely, and those who say we should not judge the atomic bombings by the morality of the present neglect the range of moral codes that were available at the time. The idea that burning civilians alive created a moral hazard was hardly unfamiliar to people in 1945, even if they did it anyway. Similarly, I will note that the people who adopt such a position of historical moral relativism never seem to apply it to nations that fought against their countries in war.

Anyway, all of the above is meant as a disclaimer, in case anyone wonders what my intent is here. It is not to argue that the leaders of 1945 necessarily ought to have done anything different than they did. It is merely to try and paint a picture of what sorts of possibilities were on the table, but were not pursued, and to try and hack away a little bit at the false dichotomy that so often characterizes this discussion — a dichotomy, I might note, that was started explicitly as a propaganda effort by the people who made the bomb and wanted to justify it against mounting criticism in the postwar. I believe that rational people can disagree on the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

What options were there for the United States regarding the atomic bomb in 1945?

Few historical events have been simultaneously second-guessed and vigorously defended as the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which occurred seventy years ago this August. To question the bombings, one must assume an implicit alternative history is possible. Those who defend the bombings always invoke the alternative of a full-scale invasion of the Japanese homeland, Operation Downfall, which would have undoubtedly caused many American and Japanese casualties. The numbers are debatable, but estimates range from the hundreds of thousands to the millions — an unpalatable option, to be sure.

But is this stark alternative the only one? That is, are the only two possible historical options available a bloody invasion of the Japanese home islands, or the dropping of two nuclear weapons on mostly-civilian cities within three days of one another, on the specific days that they were dropped? Well, not exactly. We cannot replay the past as if it were a computer simulation, and to impose present-day visions of alternatives on the past does little good. But part of the job of being a historian is to understand the variables that were in the air at the time — the choices, decisions, and serendipity that add up to what we call “historical contingency,” the places where history could have gone a different direction. To contemplate contingency is not necessarily to criticize the past, but it does seek to remove some of the “set in stone” quality of the stories we often tell about the bomb.

Varying the schedule. The military order that authorized the atomic bombings, sent out on July 25, 1945, was not specific as to the timing, other than saying that the “first special bomb” could be dropped “as soon as weather will permit visual bombing after about 3 August 1945.” Any other available bombs could be used “as soon as made ready by the project staff.” The Hiroshima mission was delayed until August 6th because of weather conditions in Japan. The Kokura mission (which became the Nagasaki mission) was originally scheduled for August 11th, but got pushed up to August 9th because it was feared that further bad weather was coming. At the very least, waiting more than three days after Hiroshima might have been humane. Three days was barely enough time for the Japanese high command to verify that the weapon used was a nuclear bomb, much less assess its impact and make strategic sense of it. Doing so may have avoided the need for the second bombing run altogether. Even if the Japanese had not surrendered, the option for using further bombs would not have gone away. President Truman himself seems to have been surprised by the rapidity with which the second bomb was dropped, issuing an order to halt further atomic bombing without his express permission.

Demonstration. Two months before Hiroshima, scientists at the University of Chicago Metallurgical Laboratory, one of the key Manhattan Project facilities, authored a report arguing that the first use of an atomic bomb should not be on an inhabited city. The committee, chaired by Nobel laureate and German exile James Franck, argued that a warning, or demonstration, of the bomb on, say, a barren island, would be a worthwhile endeavor. If the Japanese still refused to surrender, then the further use of the weapon, and its further responsibility, could be considered by an informed world community. Another attractive possibility for a demonstration could be the center of Tokyo Bay, which would be visible from the Imperial Palace but have a minimum of casualties if made to detonate high in the air. Leo Szilard, a scientist who had helped launch the bomb effort, circulated a petition signed by dozens of Manhattan Project scientists arguing for such an approach. It was considered as high as the Secretary of War, but never passed on to President Truman. J. Robert Oppenheimer, joined by three Nobel laureates who worked on the bomb, issued a report, concluding that “we can propose no technical demonstration likely to bring an end to the war; we see no acceptable alternative to direct military use.” But was it feasible? More so than most people realize. Though the US only had two atomic bombs in early August 1945, they had set up a pipeline to produce many more, and by the end of the month would have at least one more bomb ready to use, and three or four more in September. The invasion of the Japanese mainland was not scheduled until November. So by pushing back the time schedule, the US could have still had at least as many nuclear weapons to use against military targets should the demonstration had failed. The strategy of the bomb would have changed — it would have lost some of its element of “surprise” — but, at least for the Franck Report authors, that would be entirely the point.Changing the targets. The city of Hiroshima was chosen as a first target for the atomic bomb because it had not yet been bombed during the war (and in fact had been “preserved” from conventional bombing so that it could be atomic bombed), because the scientific and military advisors wanted to emphasize the power of the bomb. By using it on an ostensibly “military” target (they used scare quotes themselves!), “located in a much larger area subject to blast damage,” they hoped both to avoid looking bad if the bombing was somewhat off-target (as the Nagasaki bombing was), and so that the debut of the atomic bomb was “sufficiently spectacular” that its importance would be recognized not only by the Japanese, but the world at large. But the initial target for the bomb, discussed in 1943 (long before it was ready) was the island of Truk (now called Chuuk), an ostensibly purely military target, the Japanese equivalent of Pearl Harbor. By 1945, Chuuk had been made irrelevant, and much of Japan had already been destroyed by conventional bombing, but there were other targets that would not have been so deliberately destructive of civilian lives. As with the “demonstration,” option had the effect not been as desired, escalation was always available as a future option, rather than as the first step.

Clarifying the Potsdam Declaration. By the summer of 1945, a substantial number of the Japanese high command, including the Emperor, were looking for a diplomatic way out of the war. Their problem was that the Allies had, with the Potsdam Declaration, continued to demand “unconditional surrender,” and emphasized the need to remove “obstacles” preventing the “democratic tendencies” of the Japanese people. What did this mean, for the postwar Japanese government? To many in the high command, this sounded a lot like getting rid of the Imperial system, and the Emperor, altogether, possibly prosecuting him as a “war criminal.” For the Japanese leaders, one could no more get rid of the Emperor system and still be “Japan” than one could get rid of the US Constitution and still be “the United States of America.” During the summer, those who constituted the “Peace Party” of the high council (as opposed to the die-hard militarists, who still held a slight majority) sent out feelers to the then still-neutral Soviet Union to serve as possible mediators with the United States, hopefully negotiating an end-of-war situation that would give some guarantees as to the Emperor’s position. The Soviets rebuffed these advances (because they had already secretly agreed to enter the war on the side of the Allies), but the Americans were aware of these efforts, and Japanese attitudes towards the Emperor, because they had cracked the Japanese diplomatic code. No lesser figures than Winston Churchill and the US Secretary of War, Henry Stimson, had appealed to President Truman to clarify that the Emperor would be allowed to stay on board in a symbolic role. Truman rebuffed them, at the encouragement of his Secretary of State, James Byrnes, believing, it seems, that the perfidy of Pearl Harbor required them to grovel. It isn’t clear, of course, that this would have changed the lack of a Japanese response to the Potsdam Declaration. Even after the atomic bombings, the Japanese still tried to get clarification on the postwar role of the Emperor, dragging out hostilities another week. In the end, the Japanese did get to keep a largely-symbolic Emperor, but this was not finalized until the Occupation of Japan.Waiting for the Soviets. The planned US invasion of the Japanese homeland, Operation Downfall, was not scheduled to take place until early November 1945. So, in principle, there was no great rush to drop the bombs in early August. The Americans knew that the Soviet Union had, at their earlier encouragement, agreed to renounce their Neutrality Pact with the Japanese and declare war, invading first through Manchuria. Stalin indicated to Truman this would happen around August 15th, to which Truman noted in his diary, “Fini Japs when that comes about.” Aside from cutting Japan off from its last bastion of resources, the notion of possibly being divided into distinct Allied zones of influence, as had been Germany, would possibly be more of a direct existential threat than any damage the Americans would inflict. And, in fact, we do now know that the Soviet invasion may have weighed as heavily on the Japanese high command as did the atomic bombings, if not more so. So why didn’t Truman wait? The official reason given after the fact was that any delay whatsoever would be interpreted as wasting time, and American lives, once the atomic bomb was available. But it may also have been because Truman, and especially his Secretary of State, Byrnes, may have hoped that the war might have ended before the Soviets had entered. The Soviets had been promised several concessions, including the island of Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands (giving them unimpeded access to the Pacific Ocean) for their entry in the war, but by late July 1945, the Americans were having second thoughts. As it was, once Stalin saw that Hiroshima did not provoke an immediate response from the Japanese, he had his marshals accelerate the invasion plans, invading Manchuria just after midnight, the morning of the Nagasaki bombing.

What should we make of these “alternatives”? Not, necessarily, that those in the past should have been clairvoyant. Or that their concerns were ours: like it or not, those involved in these choices certainly ranked Japanese civilian lives lower than those of American soldiers, as is typical in war. None of the “alternatives” come with any confidence, even today, much less for those at the time, and those making the choices were working with the requirements, uncertainties, and biases inherent to their historical and political positions.But by pointing out the alternatives that were on the table, one can see the areas of choice and discretion, the different directions that history might have gone — perhaps for better, perhaps for worse. We should see this history less as a static set of “inevitable” events, or of “easy” choices, but as a more subtle collection of options, motivations, and possible outcomes

Were there alternatives to the atomic bombings?

Trinity at 70: “Now we are all sons of bitches.”

by Ahmad shah kakar , published July 17th, 2015

A quick dispatch from the road: I have been traveling this week, first to Washington, DC, and now in New Mexico, where I am posting this from. Highlights in Washington included giving a talk on nuclear history (what it was, why it was important) to a crowd of mostly-millennial, aspiring policy wonks at the State Department’s 2015 “Generation Prague” conference. A few hours after that was completed, an article I wrote on the Trinity test went online on the New Yorker’s “Elements” science blog: “The First Light of Trinity.”

Being able to write something for them has been a real capstone to the summer for me. It was a lot of work, in terms of the writing, the editing, and the fact-checking processes. But it is really a nice piece for it. I am incredibly grateful to the editor and fact-checker who worked with me on it, and gave me the opportunity to publish it. Something to check off the bucket list.

On the plane to New Mexico, I thought over what the 70th anniversary of Trinity really meant to me. I keep coming back to the post-detonation quote of Kenneth Bainbridge, the director of the Trinity project: “Now we are all sons of bitches.” It is often put in contrast with J. Robert Oppenheimer’s more grandiose, more cryptic, “Now I am become death, destroyer of worlds.” Oppenheimer clearly didn’t say this at the time of test explosion, and its meaning is often misunderstood. But Bainbridge’s quote is somewhat cryptic and easy to misunderstand as well.

Bainbridge’s quote first got a lot of exposure when it was published as part of Lansing Lamont’s 1965 book, Day of Trinity, timed for the 20th anniversary of Trinity. Lamont interviewed many of the project participants who were still alive. The book contains many errors, which many of them lamented. (The best single book on Trinity, as an aside, is Ferenc Szasz’s 1984, The Day the Sun Rose Twice, by a considerable margin.) A consequence of these errors is that a lot of the scientists interviewed wrote letters to each other to complain about them, which means they also clarified some quotes of theirs in the book. Bainbridge in particular has a number of letters related to mixed up quotes, mixed up content, and mixed up facts from the Lamont book in his personal papers kept at the Harvard University Archives, which I looked at several years back.

One of the people Bainbridge wrote to was Oppenheimer. He said he wanted to explain his “Now we are all sons of bitches” quote, to make sure Oppenheimer understood he was not trying to be offensive:

The reasons for my statement were complex but two predominated. I was saying in effect that we had all worked hard to complete a weapon which would shorten the war but posterity would not consider that phase of it and would judge the effort as the creation of an unspeakable weapon by unfeeling people. I was also saying that the weapon was terrible and those who contributed to its development must share in any condemnation of it. Those who object to the language certainly could not have lived at Trinity for any length of time.

Oppenheimer wrote back, in a letter dated 1966, just a year before his death, when he was pretty sick and in a lot of pain. It said:

When Lamont’s book on Trinity came, I first showed it to Kitty; and a moment later I heard her in the most unseemly laughter. She had found the preposterous piece about the ‘obscure lines from a sonnet of Baudelaire.’ But despite this, and all else that was wrong with it, the book was worth something to me because it recalled your words. I had not remembered them, but I did and do recall them. We do not have to explain them to anyone.1

I like Bainbridge’s explanation, because it doubles back on itself: people will think we were unfeeling and terrible for making this weapon, which makes it sound like the people are not understanding, but, actually, yes, the weapon was terrible. I think you can get away with that kind of blanket condemnation if you’re one of the people instrumental in its creation.

I have been thinking about how broadly one might want to expand the “we” in his quote. Just those at the Trinity test? Those scientists who made the bombs possible? All of the half-million involved in making the bomb, whether they knew their role or not? The United States government and population, from Roosevelt on down? The Germans, the fear of whom inspired its initial creation? The world as a whole in the 1940s? Humanity as a whole, ever?

Are we all sons of bitches, because we, as a species of sentient, intelligent, brilliant creatures have created such terrible means of doing violence to ourselves, to the extremes of potential extinction?

This is probably not what Bainbridge meant, but it is an interesting road to go down. It recalls the recent discussions about whether we live in a new era of time, the Anthropocene, and whether the Trinity test should be seen as the marker of its beginning

my firsr blog

how you doing toadya? i am doing fine i am so exited that you all come to see this aswome tutorial.

First blog post

This is your very first post. Click the Edit link to modify or delete it, or start a new post. If you like, use this post to tell readers why you started this blog and what you plan to do with it.

!["Komiya street (750 meters [from Ground Zero] before and after bombing. The archlike heavy lamp posts have fallen. One lies at the left of the lower photograph."](https://i0.wp.com/blog.nuclearsecrecy.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Hiroshima-before-and-after-Komiya-Street-600x186.jpg)

!["Prefectural Office (900 meters [from Ground Zero]) before and after the bombing. The wooden structure has collapsed and burned. Note displacement of the heavy granite blocks of the wall."](https://i0.wp.com/blog.nuclearsecrecy.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Hiroshima-before-and-after-Prefectural-Office-600x195.jpg)

![I find this one to be one of the most haunting — by filling in the missing structures, it contextualizes all of the "standard" Hiroshima photos of the rubble-filled wasteland. "Rear view of Geibi and Sumitomo Buildings before and after bombing. Taken from Fukuya Department Store (700 meters [from Ground Zero]) looking toward center. Complete destruction of wooden buildings by blast and fire. Concrete structures stand." In other places in the text, they usually point out that where you see a concrete structure like this, it has withstood the blast but was gutted by the fire.](https://i0.wp.com/blog.nuclearsecrecy.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Hiroshima-before-and-after-Geibi-and-Sumitomo-Buildings-600x205.jpg)